By Dr Kate Wilson

This blog is based on an article Kate Wilson and Charlotte Wildman are writing about illegal childminding in post-war Britain and Northern Ireland

We often understand childcare in terms of guidelines, children and carer ratios, and safety procedures. Legislation around childcare and the implications for those who breach the law are often lesser known. For example, in 2009, two policewomen fell foul of the Childcare Act 2006; they were told they faced prosecution if they did not end their reciprocal childminding arrangements after Ofsted received an anonymous tip-off that claimed illegal minding was taking place. The prosecution was eventually dropped following intervention from then-Children’s Minister Ed Balls who declared that such arrangements should not be penalised. Yet the case throws up important discussions about the impact of shifting legislation on caring arrangements and how increased regulation can have negative implications for women and their families. As part of the AHRC-funded Fellowship, ‘Reconsidering Crime in Working-Class Homes and Family Life, 1918-1979,’ we explored how care could be criminalised as a product of shifting legislation seeking to increase intervention in working-class families. We produced an article that addresses the distinct moral panic that took hold in 1970s Britain around ‘illegal’ childminding and we suggest it was typical of the ways in which the post-war welfare state reinforced and furthered hierarchies and biases around race, class and gender. Equally, this discourse around childminding shows us how the perspectives and experiences of women – particularly those from working-class, Black and migrant communities – have often been historically excluded from and even devalued in the making and unmaking of welfare reform in Britain, with other voices given precedence. This finding, we argue, has ongoing implications for current legislation around care.

The post-war era saw a renewed concern with the role of childcare and of mothers in British society. Seeking to encourage women into the workplace while also stressing their roles as caregivers, the state introduced a raft of legislation around the care of children, from the Nurseries and Childminders Act 1948, the Children Act 1948 and Children and Young Persons Act (Northern Ireland) 1950. This legislation aimed to regulate childcare practices, including childminding, while introducing fines and in some cases jail terms for those found in breach of these new rules and regulations. To enforce this legislation, local authorities were given new powers to inspect and enter people’s homes.

Care-giving became increasingly regulated by the state after the Second World War: A smiling woman with three little girls at a day nursery in the Notting Hill area of west London, circa 1958. (Photo by Frank Martin/BIPS/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

From the mid-late 1960s there was a resurgence of interest in the conditions of childminding, much of which framed this legislation as insufficient or ineffective. Much of this discussion was galvanised by disquiet around increasing numbers of working mothers seeking care for their children, with particular focus on the practices of working-class, Black and migrant mothers in Britain’s largest cities. By the 1970s, a number of academic projects emerged to investigate ‘illegal’ minding such those based at the Thomas Coram Research Unit, or led by Brian Jackson and Sonia Jackson at the Cambridge Educational Development Trust. The findings of these projects – which aimed to reveal the scale of unregistered childminding in Britain, and speculated on its potentially damaging effects on children – were feverishly and sometimes selectively reported in the press, who gave particular attention to the allegedly dehumanising conditions these ‘pin money’ minders were visiting upon their charges in cramped and rundown homes.[1] These projects and this coverage were often driven by concerns with the care of children and living conditions in Britain’s inner cities, areas which had long been subject to stigmatisation as crumbling centres of urban decay, and by the late 1960s were becoming associated with racist anxieties around migration and Black and Asian communities.[2]

Indeed, in all accounts of illegal minding, Britain’s growing West Indian community was a particular focus. Academics, MPs and journalists suggested a causal link between West Indian children’s experiences at the hands of unregistered minders and their overrepresentation in so-called schools for the ‘educationally subnormal.’ As one Home Office Circular on illegal childminding in Sheffield noted, West Indian mothers – as well as those from African and Irish communities – were increasingly leaving their children with unregistered minders, who did not receive or follow state advice on childcare, and were as a result ‘clearly handicapping their young children’s educational future.’[3]

Fears about childminding practices linked to broader concerns with the care of children and living conditions in Britain’s inner cities. Image: Manchester Inner Cities Feature, 4th February 1987, playtime at Trinity House Centre, children playing Ring a Ring a Roses. (Photo by Mervyn Berens/Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

Crucially, this suggested link failed to give due consideration to structural and entrenched racism in Britain’s schools and nurseries. According to educators, writers and campaigners like Bernard Coard, the prevalence of West Indian children in schools for the ‘educationally subnormal hinged’ on systemically racist forms of testing, teaching and placement, and biases around culture and class.[4] Similarly, in 1974, Race Today highlighted campaigns against the pseudoscientific nature of the ‘process by which children are separated and classified,’ such as IQ testing, with its disproportionate impact on Black children.[5] As the article stated, ‘The whole emphasis is on “immigrants” and their adjustment to the education system. There is no questioning of that system, of the education that black children have forced on them, be it in ESN or in ordinary schools.’[6]

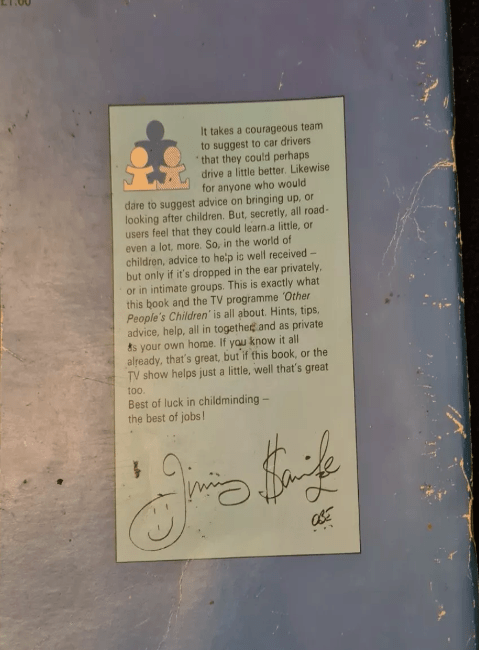

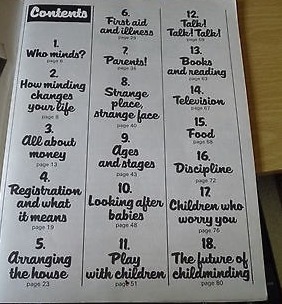

Equally, encouraging childminders to register required them to adhere to certain standards of state care, and follow guidelines not just around child safety but also around food and the home. For example, in 1976 and 1977 the BBC broadcast a nineteen-part series and published an accompanying book on childminding, both of which were fronted by Jimmy Savile. The TV show aired thrice weekly on BBC One, and the book was distributed by local authorities as a handbook for registered childminders. According to the book’s blurb – signed by Savile – it offered ‘hints, tips, advice, help, all in together and as private as your own home’ with chapters on food, discipline and arranging the house.[7]

Savile’s horrifying ubiquity in Britain’s late twentieth century media landscape is well-documented, and his involvement in public information campaigns relating to children was by no means limited to the childminding project.[8] Nonetheless, his role as the public face of this state and media intervention is both disturbing and instructive. That media darling Savile – whose abusive behaviour has been documented in enquiries such as https://downloads.bbci.co.uk/bbctrust/assets/files/pdf/our_work/dame_janet_smith_review/conclusions_summaries.pdf – served as the palatable face of childcare advice while Black and working-class women were routinely demonised in the press for their childcare practices speaks to widespread and systemic contempt for their lives, views and circumstances. Most importantly, it shows how even well-intentioned work which to some degree elides the broader structural causes of poor childcare – such as state racism and substandard housing– while privileging white, middle-class perspectives (to say nothing of Savile himself) over the voices and experiences of women from working-class and migrant communities serves to further reify racial, class and gender biases in the welfare state.

Other People’s Children: A Guide for Childminders BBC and Jimmy Saville.

Looking to women’s autonomous organising strategies in the 1970s around care tells a different story. Seminal texts published in the 1970s and 1980s, such as Bernard Coard’s How the West Indian Child Is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System (1971)and Beverley Bryan, Stella Dadzie and Suzanne Scafe’s Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain (1985) emphasised the scale and entrenched nature of institutional racism in Britain’s systems of care, from schools and nurseries to health care. In the face of these overwhelming odds, women developed their own childcare networks and organisations. These arrangements helped them navigate challenging socioeconomic circumstances which had been created and intensified by state racism, and celebrated rather than denigrated their cultural heritage. As one Manchester-based woman quoted in the Heart of the Race recounted:

The women were most vulnerable to racist attacks. The few resources we had on Moss Side, we shared. Black women set up childminding because there were no nursery places for us. We needed housing, so we tried to do something about that too. There was no demand from us on the housing department, because the authorities were racist.[9]

Such texts and interviews provide vital first-hand accounts of the distance between Black and working-class women and the institutions and interventions of the state, emphasising how women were led to develop their own organisations outwith the gaze of the state. The value and necessity of their efforts in the face of widespread demonisation and criminalisation tell an important story about the classed, gendered and racialised foundations of an increasingly punitive welfare state in mid-late twentieth century Britain.

Playgroups were important methods that allowed women to organise care away from the gaze of the state. Image: playgroup in Brixton, London, 8th February 1978. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Today, provision of childcare continues to make headlines, particularly with news that ‘Parents and carers of children aged nine months or over will be entitled to 15 hours of free childcare.’[10] For many mothers, this represents a welcome extension of state welfare. Yet as these lessons from the 1960s and 1970s demonstrate, it is important to examine what type of care is being provided, and who gets to have a say in how this care is shaped and delivered. Lessons from the past on the investigation, reporting and criminalisation of childminding highlight how design and enforcement of legislation can allow structural issues – such as poor-quality housing and institutional racism – to be reframed as cultural ones, with blame apportioned to working-class and Black women in particular for their methods of negotiating and challenging these circumstances. Equally, this moment in the post-war era reminds us of the ways in which childcare can be used reinforce certain hierarchies around cultural practices – from food to play – and intervene in women’s lives in new and sometimes unwelcome ways. We suggest that the building of equitable childcare systems necessitates a critical assessment of whose voices are included and excluded in the making of welfare, and requires us to heed important lessons on collective action and building alternatives from women themselves.

Childcare remained an important issue for women’s activism. National Campaign For Nursery Education Deliver Petition, 1972 (Photo by Ian Showell/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Dr Kate Wilson is an expert in post-1945 cultural, literary and social history. She was the PDRA on the AHRC project ‘Reconsidering Crime’ and is now a researcher on the UKRI-funded Caring Communities project at Newcastle University led by Dr Claudia Soares.

[1] Daily Mail Reporter, ‘Who’s looking after baby?’, Daily Mail, 2 May 1977, p.15.

[2] Aaron Andrews, Alistair Kefford and Daniel Warner, ‘Community, culture, crisis: the inner city in England, c. 1960–1990,’ Urban History, 50:2 (2023), pp.202-213.

[3] ‘Action in Sheffield to Meet Illegal Childminding in the Authority’, Home Office Circular, July 1974, Brian Jackson Archive, University of Essex, BJA 18 and 19.

[4] Bernard Coard, How the West Indian Child Is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain (Kingston: MacDermott Publishing, 1971).

[5] ‘Education for What’, Race Today, January 1974, p.5

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sonia Jackson, Joyce Moseley, Barbara Wheeler, David Allen, Other People’s Children: A Guide for Childminders, (London: BBC Further Education Advisory Council, 1976).

[8] Saville also fronted campaigns around children and the prevention of accidents, and road safety. R. H. Jackson, ‘Play it Safe: a Campaign for the Prevention of Children’s Accidents’, Community Development Journal, 18:2 (1983), pp.172-176; The Guardian, ‘Jimmy Savile’s ‘clunk click’ safety ads ejected from National Archives’, 12 April 2016. Accessed at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/apr/13/jimmy-savile-clunk-click-safety-ads-ejected-national-archives.

[9] Beverley Bryan, Stella Dadzie and Suzanne Scafe, Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain (London: Verso, 2018), p.xxx.

[10] Jennifer Scott, ‘Free childcare for nine-month-olds available from next week – but rollout comes with “challenges,”’ Sky News, 30 August 2024. Accessed at: https://news.sky.com/story/free-childcare-for-nine-month-olds-available-from-next-week-13205631.